My score for Solo Contrabass Clarinet, inspired by both Gerhard Richter's "Strips" paintings and Fluxus practices, offers a unique synthesis of visual art, randomness, traditional notation, and intermedia. It challenges the very notion of traditional musical composition, blurring the boundaries between auditory experience and visual interpretation, extending into a realm where technology, pictorial reflection, and radical artistic opposition converge.

Gerhard Richter’s Strips and Pictorial Expansion

Richter’s "Strips" paintings, which emerge from slicing his abstract canvases into horizontal strips and then reassembling them into new configurations, serve as the conceptual bedrock for the score. The "Strips" paintings are not mere reproductions but are fusions of past painterly gestures and digital manipulation. They acknowledge the historical baggage of painting, while actively engaging with technology's influence, a kind of digital mourning for the traditional canvas, transformed through modern tools.

The inspiration from Richter’s work can be seen as a metaphor for the digital fragmentation of experiences: the sonic and visual worlds splintered and yet reorganized into something unfamiliar, but still deeply tied to their origins. Similarly, in this score, the musical ideas are deliberately fragmented—dissected and reassembled—inviting the performer and listener to experience sonic "strips" that are constantly recombining.

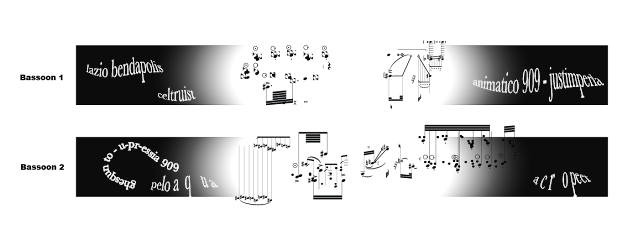

The score’s format, consisting of individual cards housed within a Fluxus-like box, mirrors this fractured yet cohesive approach. Each card, akin to Richter’s strips, provides a segment of sound, a piece of the overall structure that the performer can reassemble, much like an abstract collage of sonic moments. These moments defy linearity, embracing the Fluxus ethos of randomness and recombination.

Fluxus and the Intermedia Approach

The Fluxus movement, as described by Dick Higgins in his coining of the term "intermedia," sought to dissolve the boundaries between different forms of art—painting, music, performance, and even life itself. The Fluxus artists were deeply involved in using everyday objects, exploring chance, and breaking down the formal constraints that separated one genre from another. In this composition, the score’s DIY aesthetic, where the performer must physically interact with the cards, directly engages with Fluxus' spirit of anti-commercialism, collaboration, and experimentation.

Found materials and randomness, hallmarks of Fluxus compositions, are central to the performance. Here, the cards act as modular components—no single "right" way exists to perform the piece. The contrabass clarinet, with its broad tonal palette and capacity for extreme textures, lends itself to this improvisational style. The performer, much like an intermedia artist, must become a collaborator with the score—interpreting, organizing, and performing it with creative agency.

Technology, Pictorial Mourning, and Resistance

The idea of pictorial mourning—mourning the loss of the traditional canvas in the digital age—extends into the sonic realm in this score. The score’s use of Richter’s fragmented approach can be seen as an act of defiance against the totalizing claims of technology over art, in this case, over musical notation. Just as Richter’s "Strips" reflect the impact of digital technology on painting, this score reflects how digital culture has transformed musical composition and performance.

Here, the score does not regress into nostalgia for classical musical forms but instead confronts technology by using it to further challenge and subvert traditional musical expectations. Each card in the Fluxus box is an "act of mourning" for the disappearing boundary between sonic experience and technological mediation, yet also a celebration of the possibilities opened up by these very technologies.

The juxtaposition of quasi-traditional Western notation with photorealism also serves to reflect this confrontation. Photorealist notation, in this case, rejects the usual intent of notation to represent a world of feeling or motion and instead mirrors how a camera would capture the world—cold, detached, and exact. This detachment underscores the idea that music, like painting, has evolved under the shadow of technology and is now seen through a lens of distillation, a “camera’s” version of what we once perceived as deeply human and emotional.

The Performer’s Role and the Idea of Agency

The performer becomes more than just an interpreter—they are an active creator, engaging with the score as a dynamic, malleable construct. The "strip-like" fragments of notation and their reassembling reflect the performer's agency, much like a Fluxus artist assembling found objects into new configurations. The contrabass clarinetist, in this new score, becomes similarly empowered. They take on the role of both performer and curator, crafting a narrative from fragmented, non-linear parts.

Each card, like Richter’s strips, could be seen as a miniaturized, self-contained world. When assembled, the cards form an expansive and unpredictable sonic landscape, reflecting the performer's choices. This reciprocal oscillation between performer and notation forms the core of the piece—creating a living dialogue between sound, visual art, and performative intent.